The Fuzzy Math of Penal Substitution

One of the hallmarks of evangelical theology is the concept of penal substitution. Basically this is a form of substitutionary atonement theory which states Jesus died on the cross in place of sinners in order to satisfy the penalty of their sin. In other words, the death of Christ is substituted for the punishment sinners should receive (which is generally understood to be “death” and separation from God.) Christ takes our punishment so we can be forgiven. When you hear a pastor say “Christ died for my/your sins” what you are hearing is an articulation of substitutionary atonement.

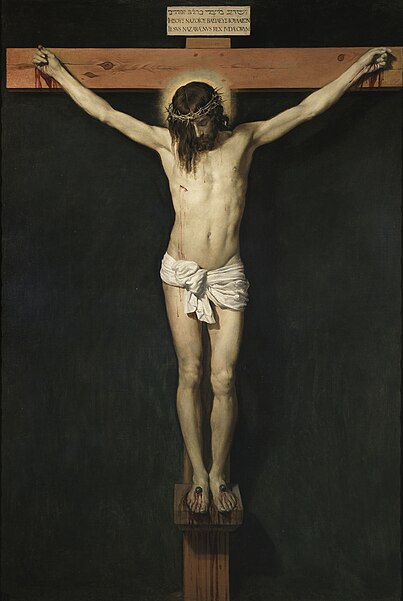

Crucifixion, D. Velázque, 17th c.

This idea of atonement has origins going back to the early church fathers, but its formal outline is generally attributed to the 11th century monk Anselm of Canterbury who preferred to talk of “satisfaction” rather than of “substitution” (Christ’s death was a satisfactory sacrifice for our sins rather than a substitution for the penalties of our sins). It was further developed and brought to wide spread acceptance by John Calvin and the reformers. It should be noted that while penal substitution is certainly favored by evangelical (especially reformed) Christians/churches/theologians, it is not the only theory of atonement. Two of the other major atonement theories are: Moral influence (Christ’s death show perfect obedience and love), and Ransom / Christus Victor (Christ was the ransom for humanity’s debt to Satan.) Other theories often combine / tweak concepts found in these approaches.

Penal substitution is based on a few premises.

- God requires punishment for our sins to be forgiven. (If you go with Anselm’s satisfaction concept, you would say God requires sacrifice for our sins to be forgiven).

- The death of Christ covers the punishment / sacrifice for all sinners.

It is with this second point that things get tricky. First, we must ask, “who is covered by this.” Those in the reformed camp will say it is only for the elect — that is, those whom God has predestined to be saved. Those in the free will camp will say it available for all, but only effective for those who trust in Jesus. Finally, those in the universalist camp will say all people are covered regardless of status. When we begin to ask who is covered by the sacrificial act of the cross, we begin to get into the fuzzy math of substitutionary atonement theory.

This leads me to a question I have pondered for years and have yet to hear a satisfactory answer:

How can the death of one person be the acceptable substitute for the sins of all humanity?

Let’s walk through the court room imagery upon which this theory is based. So I die and stand before my creator. God says to me, “It looks like you have sinned and thus you must be punished.” At that point Jesus comes in and says, “I don’t want him to be punished, since I have lived a sinless life, let me stand in his place.” Jesus is then led to the cross and crucified.

Okay, that works out great, until the next sinner comes before the throne of judgment. Presumably Jesus is allowed to stand in my place because he lived a sin free life and is the only person in the history of the world who does not deserve punishment / judgment for sin. His life for mine – its a fair trade. But now that Jesus’ perfect life has been traded for my life, what is left to be traded (substituted)?

The problems don’t stop there. If we are truly talking about the substitution of a penalty, we must examine the trade closer. In the way this theory is generally taught, we avoid damnation (judgment) because Christ voluntarily died on the cross. But, we must admit this is not a fair trade. Christ experienced physical death that lasted 3 days. Sinners on the other hand would experience eternal damnation (in addition to physical death) if it was not for the work of Christ. Again… this does not seem to be a fair trade.

So at the end of the day, the equation looks like this:

3 Days of physical death by sinless man = eternal damnation for countless people and their lifetimes of sin

I am sorry, but that math just doesn’t work out.

The books are obviously being cooked in some way. I have heard people claim that this equation still works because it was not just a man who died, but it was God himself. That seems logical, but then at the end of the day we still run into problems. How can it be a trade if God in fact did not die and did not experience damnation. The need for judgment still has not been satisfied. And, if we assume that this equation meets God’s standards so God can still be just, we must ask why it had to happen at all. If God can determine what meets the standards of a fair trade, it can be assumed that he could also waive the need for a penalty.

Now lets get back to another question: who is covered by this act? Even if somehow the math works out, and the death of one god-man can cover infinite sinful lives, then why wouldn’t this lead to universal salvation? Why must people individually accept this sacrifice? If it has the power to cover the sins of all, then why would it not be extended to all, especially if we believe God desires none to perish. (There are certainly some people who think that God does in fact desire some to perish, but that is an entirely different conversation into the nature of a loving God.)

The problem is not alleviated if you take Anselm’s view of satisfaction over substitution. It does answer a few more questions because the Old Testament does teach of a sacrafice that covers an entire group of people (i.e. on the Day of Atonement) but at the end of the day you run into the same problems concerning who is covered by this act (along with some new problems: Does God allow for, and indeed propagate, human sacrifice?).

I will be the first to admit, these are not easy questions and I do not profess to have the answers. The things we are dealing with here are of the utmost theological importance. We are talking about the very nature of Christ, his mission, and its effect on our relationship with God. When we talk about atonement, we are talking about how God interacts with and responds to humanity and vice versa. This is no minor matter.

But at the same time, I fear we have all to often assumed the only orthodox understanding of atonement is that of penal substitution without first examining the workings of such a theory. Its not that I reject this approach, its that I don’t understand it. This post is a sincere effort to work through my questions and I invite all my friends who take this approach to help me understand it.

Hi Ben,

Thanks for sharing your thoughts on this topic. I, too, have wrestled and struggled with the idea of the atonement for quite some time. To be more specific, I especially struggle with the violent nature of it (torture and death) and what that means for God’s character if God required or even desired it.

You raised the issue of the value of Christ’s sacrifice in comparison to the debt required. In “Cur Deus Homo,” Anselm argues that the debt humanity owes is so great that only God can pay it, but that God, who is inifitely good, is indeed able to pay the debt of even a great bad.

Coming from a Wesleyan background, I have always had trouble with the Reformed position of a limited atonement. I tend to move back and forth between an Arminian position and universalism, probably coming out somewhere in the neighborhood of atonement for all unless rejected by the individual.

I tend to gravitate more toward a Christus Victor view of the atonement, which I think is more faithful to Scripture and the writings of the early church. I do find some value in both the subsitutionary and moral influence models, though, and in the end, tend to have a more kaleidoscopic view than anything else.

@John Hill

Good stuff John… I too lean towards a “kaleidoscopic” understanding of the cross. At a minimum (and perhaps at a maximum as well) I think the cross represents the climax of the incarnation and thus holds extreme importance.

First off, you guys are way too smart for me. Interesting post to say the least. I agree that it’s hard to know the specifics of what Christ’s death did. Meaning, how does it really unlock salvation. I know about the substitute for sin, but it is an incredible thought.

Earlier you said that the math doesn’t add up about basically a “one death for all” substitution. I agree, but in a different way. For a God that created the universe, knows the thoughts on each of our lips before we say them, listens to our prayers, etc; one death seems more than enough.

I think the death was enough for everybody in the world. Christ’s death has the potential to cover all sins. Basically, we have to repent and call upon Christ to have access to that forgiveness. It’s the most important action in the history of the world, so don’t let this next silly example lower that. Let’s say Sonic is giving free root beer floats out to everybody, which by the way they did, and was great. Even though everybody has access to the free float, you have to go get it. The analogy is actually pretty deeper than that. Everybody in our church was calling people letting them know about these free floats, making it a fun church social after Wednesday night service. The sad part is that none of us were talking about the gift of salvation, which is slightly more important.

Anyway, all that made sense in my head. Sorry if its mush. I too am a part-time stay at home father, so when all else fails, blame the baby for my stupidity.

Take care.

Let me say again… I don’t have the answers to this… but I certainly have questions.

Eric, I agree with your comment:, “For a God that created the universe, knows the thoughts on each of our lips before we say them, listens to our prayers, etc; one death seems more than enough.” But that brings me to my next point… if God can make one death sufficient for all of humanity, then why must their be the death at all?

I also agree with you on how an act can cover everyone, and not be taken advantage of by everyone… but couldn’t we repent and accept God’s forgiveness without Christ having to die?

Why did Christ have to die? If you answer it is to cover the sins of the world, then I argue the math doesn’t add up, and if you say God does his own math, then I ask why God requires a death at all.

I agree that the cross is the most important moment in the history of humanity… but I am not yet convinced it holds this status because it represents some cosmic transaction.

On to other things… I did not realize (or remember) that you were doing the stay at home dad thing. How is that going for you? What does your work schedule / care schedule look like?

Ben,

This is certainly a thought provoking piece.

I’m assuming from this piece that you see God as strictly a judge/juror/executioner? While I know the Bible tells us that ultimately God will have the final judgment and we are not to judge because of this, it seems presumptuous to believe that God is completely legalistic and cares only about our laundry list of sins and looking at a 1-for-1 replacement.

Paul even went so far as to say that from a legal standpoint, he himself was “faultless,” and that had led him nowhere as a Christian, right? It seems that Paul’s writings were more about living like Christ, of striving towards that perfect example, and therefore coming into a closer relationship with the Lord as a result. Or, that’s how I see it…

You obviously have FAR more study and thought into this subject that I’ve ever considered (I’m going on about 25 minutes now!), but I see Christ’s death on the cross as a sacrifice to show us – sinners – how to ultimately live as a LIVING sacrifice and to give us the doorway to salvation through God’s perfect plan.

Is there anywhere in the Bible that specifies that God requires some kind of a 1-for-1 trade off for the death of Christ? (If so, I’m unfamiliar.) It isn’t as if Christ came and died in some flurry of tragic and unforeseen events; it was God the father who sent his Son to die and have our lives intertwined into theirs through the Holy Spirit. If God had the intent to make the Cosmic Math Equation work out, he would have at the very least sent more than one Christ, don’t you think?

Hey Isaac,

I actually don’t see God as simply judge/juror/executioner and that is part of the reason why I have problems with penal substitution. At the end of the day, I am probably come down very close to the understanding you articulated (which by the way, is most similar to moral influence theory).

Hebrews probably elaborates more on this issue than any other New Testament book. What I just noticed is that this very point is what prompts the writer’s tough love in 5:11: “We have much to say about this, but it is hard to explain because you are slow to learn.” Even so, the writer goes into more detail in chapters 7-10.

As far as I can tell–from my reading of Hebrews–this is the long and short of it:

Jesus was the kind of person whose blood was enough. It was enough. It was enough to counterbalance “eternal damnation for countless people and their lifetimes of sin.” Immediately, we think, “Wow, that must be a very special kind of person with some very special blood.” Well, the Bible–not only in Hebrews–spends a lot of time trying to convince us of that point: Yes, that kind of person was very special. He was very, very special. In fact, there’s only been one of that kind of person in the whole history of persons.

Hebrews 9:22 says “The law requires that nearly everything be cleansed with blood, and without the shedding of blood there is no forgiveness.” It seems strange and barbaric, but blood is what makes God forgive sins. Call it redemption, or payment, or counterbalancing the sin equation. Regardless, the all-important word is actually a verb: forgive. The action we want God to do: forgive. And blood is what makes God do that. If people in the old system wanted God to do some forgiving, they had to shed some blood. Yes, it sounds awful, but Hebrews 10:11 is probably worth mentioning. It points out that blood-shedding was something that–in the old system–had to happen “again and again.” Not so in the new system. Apparently, that was a miserable cycle for everybody involved–God included.

Hebrews 9:28 says that “Christ was sacrificed once to take away the sins of many people,” and 7:27 says that “He sacrificed for their sins once for all when he offered himself.” When it comes to cleansing us from our sin, it wasn’t the length of his stay in the grave that mattered. It was the one-time shedding of his sinless, untainted, more-precious-than-usual blood.* In other words, Jesus’ blood was a more effective forgiveness-causer than ordinary blood. The writer doesn’t say how much blood was needed–only that enough was shed and that it only had to be done that one time.

Ultimately, the New Testament describes a strange causal process and then asks, “Now, do you have faith that x causes y?” We are asked to have faith that Jesus’ blood makes God forgive. We may question God’s math, but it’s not really about math. It’s about what God does for us and what prompts him to do it: in this case, the blood of Jesus. And I think we’re supposed to believe that the process–as strange as it sounds–actually does work.

Why God requires us to have faith in the process before we can get involved in it personally–that’s another question.

*A sidenote: I remember an old Carman song called “The Champion” that depicts Satan as stunned with “unexpected horror” to discover Jesus rising again. It’s an interesting point. Is it surprising that Jesus’ death would be followed by a Resurrection? Yes. But is it against the rules? No. And what right does Satan have to complain? Like us, he is a creature and participant in creation. He is not the creator. He is not the forgiver. Satan is not the one who is offended by sin. He is merely the accuser, the one who presses God to remember our sins. He’s the ultimate mall cop, and when it comes to God’s forgiveness, “no fair” is probably his motto.

@Mark M.

Good stuff Mark… thanks for taking the time to really flesh out your thoughts. You have presented a well reasoned and researched response.

Students of scripture should not be turned off by the concept of sacrifice and blood – it is one of the dominate themes of the OT. And as you have pointed out, the author of Hebrews certainly understands the death of Christ to be the sacrifice par excellence.

What is interesting about your comments/discussion/argument is that they effectively stand against penal substitution. To say Christ’s death is a sacrifice for our sins is quite difference than arguing that Christ stood in our place and received our punishment. Noting the sacrificial role of the cross is much more similar to the satisfaction theory than the substitution theory (although they are obviously linked).

I’m reminded of CS Lewis’ comment that the atonement, much like your dinner, doesn’t have to be understood completely to be nourishing. Understanding helps. He goes with the moral influence theory which I believe is part of the mix. The cross has inspired great acts of self-giving love and has been a powerful moral influence. But as others have said, Christus Victor is a critical fascade as well.

One more thought – many of the things we believe deeply we cannot fully rationally account for. Take memory beliefs: I can never prove a single memory belief is warranted yet I trust I am warranted to believe them. Certain spiritual beliefs also arise in my mind as I believe in God and read scripture. Not being able to account for it perfectly isn’t evidence against it necessarily. This doesn’t mean our faith is irrational. On the contrary, rationality does play a limited role, but what we believe vastly exceeds what we can rationally account for on almost all levels of our belief systems. Rationality points the way but belief goes the extra mile.

I had a great phone conversation with Mark this evening and we talked about how our understanding of the cross must include all these elements.

I find the concept of penal substitution can be used by people as a litmus test of beliefs. That is unfortunate. We should not limit, but rather constantly probe the depths of the meaning of the cross.

This is a great discussion! I appreciate Mark’s comments and use of the book of Hebrews. For me, one of the real sticking points has to do with 9:22b – “without the shedding of blood there is no forgiveness of sins.” Why? Why does blood have to be shed for forgiveness to occur? Why something so violent and barbaric? Is it to remind us of the seriousness of sin? Is there some kind of cosmic balancing game where life is truly traded for life? Didn’t Jesus push us away from that kind of thinking (no longer an eye for an eye)?

Talking about forgiveness, Mark wrote, “And blood is what makes God do that.” I’m not so sure that something we do can MAKE God do anything – if anyone has free will and is not bound by what others do, it is God. Our forgiveness cannot be a forced transaction and still be grace, can it? So, that still leaves me wrestling with this idea of violent bloodshed being necessary or even simply part of forgiveness. Why is blood required for forgiveness?

The problems with the penal substitution theory was one of the major reasons why I de-converted from evangelical theology. I have been explaining the problems and the “answers” given by evangelical theologians. You might find it helpful.

formerfundy.blogspot.com

Thanks for the comment Ken. I fear way too many people take PST for granted without ever really thinking through it. Feel free to link to my post in your blog if you want to.

“It is not those who hear the law who are righteous in God’s sight, but it is those who obey the law who will be declared righteous.” Rom. 2:13

A Word of law has been added to the law by Jesus’ crucifixion. See Rom. 5:20 & Heb. 7:12b. Therefore no person will be saved from the penalty of the law by not obeying this law which has been added.