Tutu on “Religious Human Rights and the Bible”

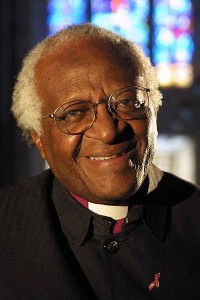

I few weeks ago I wrote a post discussing health care as a right. Since then I have had several good conversations with people from across the political spectrum on what constitutes a “human right” and what the implications are of such a delineation. Last night I came across a 1996 article by Archbishop Desmond Tutu (a hero of mine) entitled Religious Human Rights and the Bible. In just a few short pages he frames the question brilliantly by exploring how the Christian worldview calls us to understand the importance and dignity of each human being.

Tutu begins by acknowledging that religion (especially Christianity) has led to oppression and injustice. Yet, he is quick to counter by pointing out the narrative of Scripture calls for a different view of things. He bases his argument on the implications of the creation story where all humanity is uniquely created in the image of God. He says:

The Bible claims for all human beings this exalted status that we are all, each one of us, created in the divine image, that it has nothing to do with this or that extraneous attribute which by the nature of the case, can be possessed by only some people… We must therefore have a deep reverence for the sanctity of human life… The life of every human person is inviolable a gift from God.

Being created in the image of God is not just about identity Tutu contends, it is also about calling and purpose.

The [Biblical Narrative] declares that the human being created in the image of God is meant to be God’s viceroy, God’s representative in having rule over the rest of creation on behalf of God. To have dominion, not in an authoritarian and destructive manner, but to hold sway as God would hold sway–compassionately, gently, caringly, enabling each part of creation to come fully into its own and to realize its potential for the good of the whole, contributing to the harmony and unity which was God’s intention for the whole of creation.

When we understand ourselves and others in light of our connection with God, it requires a different response to questions about humanity and the rights of all persons.

[This understanding] imbues each one of us with profound dignity and worth… In the face of injustice and oppression it is to disobey God not to stand up in opposition to that injustice and that oppression Any violation of the rights of God’s stand-in cries out to be condemned and to be redressed, and all people of good will must be engaged in upholding and persevering those rights as a religious duty. Such a discussion as this one should therefore not be merely an academic exercise in the most pejorative sense. It must be able to galvanize participants with a zeal to be active protectors of the rights of persons.

Even if we capture the depth and breadth of the implications of this understanding of God and his people, we are still faced with the fact that humanity was given the freedom to choose right or wrong, good or evil, obedience or rebellion. We must not only understand who we are in light of our creator, we must also walk the delicate line of what it means to embody this reality. Tutu explains:

We are created to exist in a delicate network of interdependence with fellow human beings and the rest of God’s creation. All sorts of things go horribly wrong when we break this fundamental of our being. Then we are no longer appalled as we should be that vast sums are spent on budgets of death and destruction, when a tiny fraction of those sums would ensure that God’s children everywhere would have a clean supply of water, adequate health care, proper housing and education, enough to eat and to war.

Tutu contends that it is only when we are willing to first understand ourselves and others in light of our relationship with God and our role as bearers-of-the-image-of-God, that we are truly able to to grasp the dignity, worth and inherent rights of all persons. He concludes:

The biblical understanding of being human includes freedom from fear and insecurity, freedom from penury and want, freedom of association and movement, because we would live ideally in the kind of society that is characterized by these attributes. It would be a caring and compassionate, a sharing and gentle society in which, like God, the strongest would be concerned about the welfare of the weakest, represented in ancient society by the widow, the alien, and the orphan. It would be a society in which you reflected the holiness of God not by ritual purity and cultic correctness, but by the fact that when you gleaned your harvest, you left something behind for the poor, the unemployed, the marginalized ones–all a declaration of the unique worth of persons that does not hinge on their economic, social, or political status but simply on the fact that they are persons created in God’s image. That is what invests them with their preciousness and from this stems all kinds of rights.

Tutu’s analysis is poignant and thought provoking — especially for Christians. It is not adequate to define human rights in terms of the constitution or any body of law. Likewise, we cannot base our decisions on what is right on economic models or political ideologies. Instead, we must ask a different sort of question. We must inquire as to how we can love and care for all people — all of whom are created in the image of God.

All marks of emphasis in quotations are mine. Religious Human Rights and the Bible was originally published in Volume 10 of the Emory International Law Review. You can download the complete file here from The Center for the Study of Law and Religion at Emory University.

I love this. Well done. I was really touched when I read “We are created to exist in a delicate network of interdependence with fellow human beings and the rest of God’s creation. ” I have said for years to other people Christians and non, that I believe “that people are meant to be used. Used to their fullest potential based on the gifts that God has given them.” “a delicate network of interdependence with fellow human beings ” is exactly what I’m talking about. I believe that if these gifts are used with good intent (ie. when you gleaned your harvest, you left something behind for the poor, the unemployed, the marginalized ones–all a declaration of the unique worth of persons that does not hinge on their economic, social, or political status but simply on the fact that they are persons created in God’s image.) an incredible balance of human health, wealth, and integrity can be achieved. Bravo on the article Ben, great choice.

Thanks Joe.

I have been reading several of Tutu’s articles the last few days. Many of them are really good (especially the ones on forgiveness and reconciliation), but this article struck a special chord for me.

-bk

I’m not sure if I’m the person you’re interested in…

I find it interested that Tutu goes to the one of the central passages that Dominion Theology uses to support itself. To me, it’s a very risky move – quite the gambit actually – but pays off for his ideas. To me, the question is: Does the definition of religious-based human rights depend on that passage? Would the argument be just as strong without using that passage? What benefits are gained my the (as I’ll call it, for lack of knowledge of a better term…) the “Dominion Passage?” I’ll give my thoughts and let you judge if they’re interesting…

I’ll go in reverse order of the questions – it seems most logical to me… (I’m using lots of ellipsis because I found a new way to type them)

“What benefits are gained by using the ‘Dominion Passage’?”

I must admit, again, that the use of this passage in human rights shows the unique and daring perspective that Tutu seems to take (biblically) on the matter. At first reading to me, the passaged deals with our duties and the rights of those we are given dominion over (“lesser” beings). This passage has been used a great deal by the “green church” and has been in my mind due to that… but back to the question. From Tutu’s perspective, we see ourselves as surrogates for the (and I think this is critical in Tutu’s reading) rule of God. I love the term viceroy, again, interesting and brilliant. This reading places us not just above the animals on the level of consciousness, but on the level of purpose – we are not just rulers, but temporary rulers. Yet, up to this point, I haven’t yet discussed the rights of one to the other. This is where Tutu’s gambit is (from my reading) and the big payoff of the gambit is. Instead of simply stating that the ruling class (awkward but applicable perhaps…) has responsibilities to the lower classes, the ruling class has tasks for itself. There are myriad corollaries and reasons for this, and seem pointless to go into without a specific need. This strikes me as a fascinating perspective – and one that draws explicitly on the Christian heritage Tutu is coming from. Tutu’s gambit leads him down a path that would be far more difficult to reach from a philosophical perspective – even the Kantian perspective. (Does that need explanation? I could see it needing it, but at this moment I don’t much desire to explain unless mandatory.) Instead of relying on being made in God’s image, he relies on the fact that our task is to ACT in God’s image. This implication is far more complex than any that are proposed in, say, the Beatitudes. Most of the rights being discussed are human – human. The human-human rights Tutu leads to deal with dominion, not creation.

“Would the argument be stronger without using the passage?”

I must admit, I posed quite the question here. It’s hard for me to say at the moment. It is true that the unique (well… at least to me) perspective leads me to a new (and it strikes me, very Christian) way of seeing rights. We have dominion, ergo, we have rights. Perhaps this is best left up to someone with stronger feelings on the matter. I don’t think there is a necessity for this passage – to me, the fact we have rights and should respect them comes from the issue that we are all human. Tutu expands that to the fact we are viceroys. In essence, we are commanded to be God-like (I’m not implying a false godship, simply the expansive attributes) to those we are given dominion over. Ergo, we must remain God-like to each other. Feel free to blow this out of the water. I’m just thinking out loud.

“Does the definition of religious-based human rights depend on this passage?”

No. I don’t think we should depend on this passage for that. Again, disagree wholeheartedly with me, I really am thinking out loud. It strikes me that this is what Christians should use to set themselves apart – the carrying the soldier’s load for the extra mile – from non-Christians. Tutu allows for the respect we should pay that which we have dominion over to also be shown with mutual respect to each other. From my reading though, it seems that the Christian should desire for all others to have the same rights they feel are mandated to them. Complex in our world (as it should be) due to the fact we have classes, countries, and politics. I don’t see, from my self discussion, any reason to deny a human a right that would show benevolence.

Of course, this is my mindless musing upon a complex and divisive issue. Of great interest to me would be the thoughts of someone who associates themselves with Dominion Theology. Wouldn’t that be interesting? I’ve never really discussed much at length with someone I knew was at Dominion Theology supporter. I’d love to know if this is copacetic with their beliefs?

I hope something in here is worthy of a little interest. I just found the manner of dealing with that verse unique – and quite the gambit!

I also find the fact that my emoticon was turned into a scary little yellow guy funny – and disturbing.

Hey Aaron,

I think all your points are valid, but I am going to undercut some of your arguments. I don’t think Tutu’s use of the Genesis passage is primarily to connect humanity to the idea of dominion. Instead, I think his emphasis is on the concept of “image-bearers.” Humans have rights because they carry the image of God — to withhold rights from people is a sin against God. Of course by using the opening to Genesis he taps into a multi-faceted concept.

I certainly think Tutu could have made the argument without using this passage, but I think Genesis 1-2 are particularly powerful because they are used by the author(s) to frame the entirety of scripture. (I could get into the implications of JEDP and how the exilic/post-exilic influence serves to shape not only this passage, but Hebrew Scriptures as a whole, but that might be a bit much for a late night like this.)

Anyway, I think Tutu’s argument could be contained in a pretty simple way: ALL humans have rights because of their intimate connection with YHWH.

Thanks for the thoughts… you are always welcome (and encouraged to comment).

Hmm…

I think I simply worded things too strongly. I don’t believe that Tutu is intentionally connecting the concept of dominion in the passage – but the implications are there. If one is to blend the idea of image-bearer and dominion together (a fun idea in and of itself) it could be seen as they are different applications of the same development of the same idea. It strikes me (and again – I’m one who looks for things that may not be intended, but exist) that the “image-bearer” is simply one aspect of a dominion idea. Simply (and quite crudely) put – because we are “image-bearers” we have dominion (or is it vice versa – I forget…). You’re right (of course!) that Genesis is quite multifaceted (look at prismatic theology…) but I don’t see a separation there – it’s two facets of the same thing.

Re-reading my post leads me to the same conclusions you did – I did write too hastily (calling it a “gambit” surely made it sound intentional) so I definitely needed more clarity. Essentially, to me it doesn’t matter if Tutu intended it if it is there. Of course, I don’t mean that Tutu would necessarily endorse what I said (and wouldn’t expect that), but it is a possible corollary from his statements. Also, I might be willing to actually defend this position – if I actually felt like I could throw myself behind it!

@Aaron Stepp Aaron, this post is almost a year old, but in Googling the term, Prismatic Theology, I stumbled upon the conversation which I thoroughly enjoyed reading. As the author/scholar who is pioneering the Prismatic method of study, I’m curious as to how you heard about it’s connection to Genesis 1.

What is the Bibles relationship with human rights? Discuss.

Conditional or unconditional?

If conditional, conditional upon what?

Conditional upon fealty to The Most High?

If so are the qualities of the Most High immutably fixed, or does his form & elements change at each stage or phase of human development?

……………………….

Firstly I wish to state my own position, I no more believe in unconditional free rights than I believe in unconditional free beer. Thus, I do not subscribe to the enthusiasm expressed by some writers on the recent growth off the ~rights without responsibilities~ society.

In the Bible, Exodus & Deuteronomy are the first books to inform us about basic rights. They are also books which inform us on a significant increase in our responsibilities. In sum rights are a reward for meeting responsibilities, they are neither free nor universal. Ultimately, the first commandment is central… You shall not worship any other god but YHWH. All Biblical rights are dependent on this first commandment. The American declaration ~all men~ (no matter what their God) has a problem.

Mostly the Bible posits rights as a reward for reciprocal fealty to the Most High. Yet this most high is specified only in honorifics & generalities, he is never specified in specifics. Attesting this Most High is the highest man can know at any current level of human development. As man develops & adapts to changing conditions the highest he can currently know keeps changing form. Thus the Most High is never specified in specifics which would date him to a fixed period or bind him to any current level of understanding. He remains the Most High God of Israel; always the highest we can know no matter what our current level of development.

As his own elements keep changing according to our levels of development, our levels of rights are variable also. Man can no more proclaim a bill of fixed rights than he can proclaim a bill of fixed responsibilities. If everything keeps moving, there can be no such thing in either event. All we can proclaim, & what the Bible does proclaim, is the generic principle that rights are dependent on reciprocal fealty to the Most High, in whatever form said reciprocal fealty make take in our time & period.

Ken Maynard. e-mail… communichristi@gmail.com NZ… 021 2517 501.

Link to Home-page… http://www.communichristi.org.nz